Well, while we wait patiently for the ladies to begin earning their keep, we are in the same boat as most everybody else when it comes to eggs. We are still getting our weekly delivery of farm-fresh eggs with our veggie box once a week—which, with their orangey yolks and stiff whites, have turned us into egg snobs as it is—but that delicious dozen barely lasts us to the weekend, when pancakes or herbed baked eggs usually puts us over the top. So once in a while we still find ourselves staring at the expanding grocery store fridge, wondering how to choose. Organic? Free range? Pastured? Omega-3, wha?

What’s in a name?

It turns out that only a few of the typical labels are regulated. Here’s a breakdown, according to the Humane Society of the United States (emphasis mine, with my notes added beneath each):

Certified Organic

HSUS: “The birds are uncaged inside barns, and are required to have outdoor access, but the amount, duration, and quality of outdoor access is undefined. They are fed an organic, all-vegetarian diet free of antibiotics and pesticides, as required by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Program. Beak cutting and forced molting through starvation are permitted. Compliance is verified through third-party auditing.”

Between the lines: Certified Organic is definitely the best of what’s out there being regulated in the mainstream, but even if you ignore the icky bits (“permitted” beak cutting and forced molting?!), there’s some nuance to be aware of here. Vegetarian diets are a hallmark of organic livestock, intended to keep cows and pigs from being fed animal byproducts back to them and thereby promoting disease. Duh, that’s awesome! The sad thing is, chickens aren’t vegetarians – they are omnivores, like us, and in fact need lots protein to produce an egg a day. When they’re fed vegetarian diets, they usually get most of all of their protein from cheapo soy, which a) promotes a monoculture, b) doesn’t represent the natural, varied of a happy hen, and c) results in runny whites and pale yolks (visual evidence we’re not getting the most nutritious egg on our end of things). But an nuanced diet isn’t as easy to regulate as a blanket restriction.

In addition, the access part is mostly lip service – usually this means there’s a door somewhere in the barn wall leading to an outdoor space, which the hens are theoretically free to roam in at will. But chickens are creatures of habit and group-think, so if they’ve not been shown explicitly that they can exit through that door by a human or another chicken, it’s unlikely a hen will ever venture there on her own, if she ever came across it. And if she did, it might turn out to be a tiny concrete pad.

Free Range (or Free-Roaming)

HSUS: “While the USDA has defined the meaning of “free-range” for some poultry products, there are no standards in “free-range” egg production. Typically, free-range hens are uncaged inside barns and have some degree of outdoor access, but there are no requirements for the amount, duration or quality of outdoor access. Since they are not caged, they can engage in many natural behaviors such as nesting and foraging. There are no restrictions regarding what the birds can be fed. Beak cutting and forced molting through starvation are permitted. There is no third-party auditing.”

Between the lines: Gah, I want this one to be real! It has so much potential. But it’s not audited, which means it’s not really regulated. So unless you know what exactly “free range” means to a given farm or producer, this one is pure marketing speak, plain and simple; the burden’s on you as the consumer to figure it out. Main thing that confuses most folks: Free Range is NOT the same as, and definitely does not imply, Organic.

Cage-Free

HSUS: “As the term implies, hens laying eggs labeled as “cage-free” are uncaged inside barns, but they generally do not have access to the outdoors. They can engage in many of their natural behaviors such as walking, nesting and spreading their wings. Beak cutting is permitted. There is no third-party auditing.”

Between the lines: These birds are kept in warehouses or barns, just like Free Ranged birds, but with no outdoor access, and the label has the same issues as Free Range – no auditing means little accountability. But better than conventional.

Vegetarian-Fed

HSUS: “These birds’ feed does not contain animal byproducts, but this label does not have significant relevance to the animals’ living conditions.”

Between the lines: As mentioned above, chickens aren’t vegetarians! But lack of animal byproducts is worth the trade-off, so Veg-Fed is recommended. This also does not imply pesticide-free or antibiotic-free, but if you’re already buying Organic, this additional label is superfluous.

Fertile

HSUS: “These eggs were laid by hens who lived with roosters, meaning they most likely were not caged.”

Natural

HSUS: “This label claim has no relevance to animal welfare.”

Omega-3 Enriched

HSUS: “This label claim has no relevance to animal welfare.”

Between the lines: These birds were fed fish oil or flaxseed, which actually is awesome and part of the varied diet I talk about above. We feed our hens flaxseed for the fatty acids it’s supposed to impart to the eggs! But yet again, this is not regulated, so there’s no way to know how much of these supplements the hens are fed.

Certified Humane

HSUS: “The birds are uncaged inside barns but may be kept indoors at all times. They must be able to perform natural behaviors such as nesting, perching, and dust bathing. There are requirements for stocking density and number of perches and nesting boxes. Forced molting through starvation is prohibited, but beak cutting is allowed. Compliance is verified through third-party auditing. Certified Humane is a program of Humane Farm Animal Care.”

Between the lines: I haven’t seen this one much, but I think it’s on the rise, and it sounds pretty good to me. Providing for a chicken to be able to act like a chicken is an amazing step in acknowledging that these birds are living beings, not machines. The beak cutting bit sucks, and indicates that this method still gives rise to behavioral issues (hens in subpar conditions will peck each other and can cause serious injury), but if done properly at an early age, apparently it’s over and done with, not an ongoing issue like starvation or cramped quarters.

United Egg Producers Certified

HSUS: “The overwhelming majority of the U.S. egg industry complies with this voluntary program, which permits routine cruel and inhumane factory farm practices. Hens laying these eggs have 67 square inches of cage space per bird, less area than a sheet of paper. The hens are confined in restrictive, barren battery cages and cannot perform many of their natural behaviors, including perching, nesting, foraging or even spreading their wings. Compliance is verified through third-party auditing. Forced molting through starvation is prohibited, but beak cutting is allowed. This is a program of the United Egg Producers.”

Between the lines: It’s a trap! This is far and away regarded as the worst and most misleading label, with its checkmark and “compliance” language. Do not buy based on this logo.

Turns out there are all kinds of interesting things to know about eggs and some can really help with informed decisions at the grocery or farmer’s market. Starting with freshness:

The lore goes that the fresher the egg, the better, and while there’s obviously more to it than that, we may as well start there.

How fresh is this egg?

Method 1: Get physical.

There’s a rather well-known way to measure how fresh an egg is with just the egg and a glass of water. Maybe you’ve heard of it – it’s well-documented elsewhere and I don’t have old eggs on hand to test it out, so I won’t post photos of it here. But it basically involves putting an egg in a glass of water and watching to see how it comes to rest. If the egg lies flat along the bottom of the glass, it’s supposedly fresh; if it stands upright but still sinks, it’s ok but a little older; and if it floats, ick, it’s super-old and don’t eat it!

This works because every egg has an air sac at one end. As the egg gets older, the white loses moisture (eggshells are porous) and the sac gets bigger, causing the egg to become more buoyant. But eggsperts (ha!) will tell you this method isn’t foolproof, because every egg is laid with a different size sac, so occasionally a fresh egg will read like an older one, and vice versa. If the eggs are still in the carton, you might instead try…

Method 2: Crack the code.

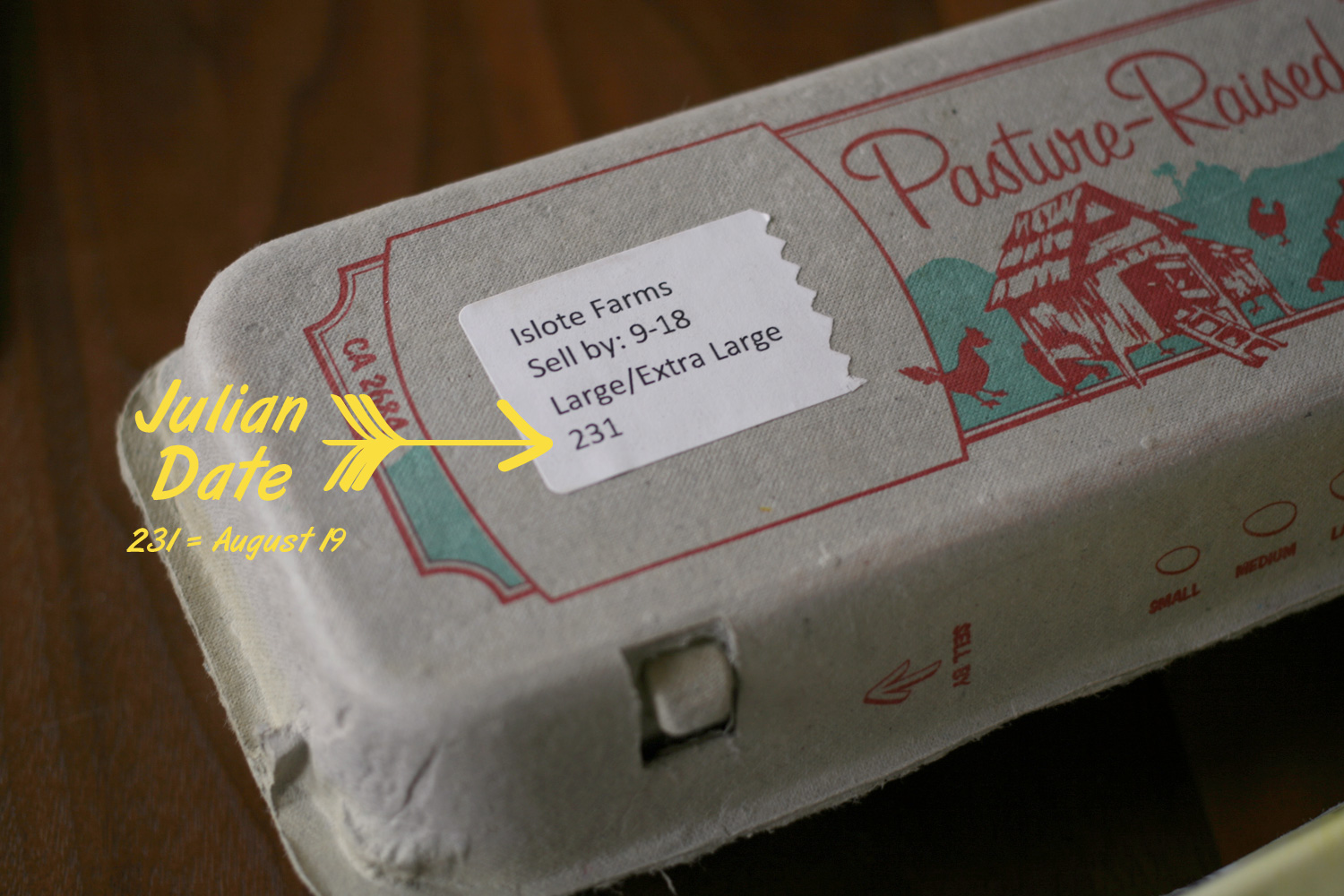

Don’t worry, it’s a very easy code, once you know what to look for! Surely you’re familiar with the sell-by date. Turns out that’s just a red herring in our quest for freshness. Pass right over that one and instead seek out a three-digit number between 001 and 366, which the food industry refers to as the Julian Date (apparently it’s actually an ordinal date).

In the US, every egg or carton is required to be stamped with the Julian date on which the eggs were cleaned and packed, and each number corresponds to the day of the current year – eggs marked 001 would have been packed on January 1, while my carton of eggs below was packed on July 7. Check my calculation here (PDF) – see? Easy!

Of course, the date an egg was gathered and packed may be a little later than the date it was laid, depending on the operation. So add a couple days, and you realize the sell-by date is more than a generous a month away. Do some grocery store calculations and you’ll see many store brand eggs sell eggs up to six weeks old! The shortcut is to simply grab the highest number you can find amongst those on offer – they’ll have been packed most recently.

This website, you can discover a great variety of slot machines from famous studios.

Players can enjoy retro-style games as well as modern video slots with stunning graphics and bonus rounds.

Even if you’re new or an experienced player, there’s a game that fits your style.

money casino

All slot machines are instantly accessible anytime and designed for laptops and tablets alike.

You don’t need to install anything, so you can jump into the action right away.

The interface is intuitive, making it simple to explore new games.

Join the fun, and enjoy the excitement of spinning reels!

La nostra piattaforma permette la selezione di operatori per attività a rischio.

Gli utenti possono trovare professionisti specializzati per missioni singole.

Gli operatori proposti vengono scelti con cura.

sonsofanarchy-italia.com

Con il nostro aiuto è possibile leggere recensioni prima di procedere.

La fiducia rimane un nostro impegno.

Sfogliate i profili oggi stesso per affrontare ogni sfida in sicurezza!

On this site, you can discover trusted CS:GO gaming sites.

We have collected a selection of gaming platforms dedicated to Counter-Strike: Global Offensive.

All the platforms is handpicked to provide safety.

legit csgo gambling sites

Whether you’re new to betting, you’ll easily select a platform that matches your preferences.

Our goal is to make it easy for you to access only the best CS:GO betting sites.

Start browsing our list right away and enhance your CS:GO playing experience!

This website allows you to connect with workers for short-term risky tasks.

Visitors are able to securely request services for unique requirements.

Each professional are qualified in managing intense tasks.

hitman-assassin-killer.com

This site provides secure arrangements between employers and contractors.

Whether you need urgent assistance, this platform is the perfect place.

List your task and find a fit with the right person now!

Questo sito offre l’assunzione di lavoratori per lavori pericolosi.

Gli utenti possono ingaggiare operatori competenti per incarichi occasionali.

Le persone disponibili sono selezionati con severi controlli.

sonsofanarchy-italia.com

Sul sito è possibile ottenere informazioni dettagliate prima di assumere.

La qualità rimane un nostro valore fondamentale.

Esplorate le offerte oggi stesso per trovare il supporto necessario!

Our service lets you connect with experts for temporary risky missions.

Clients may securely arrange services for unique situations.

All listed individuals are qualified in executing complex tasks.

hire an assassin

This site guarantees private communication between users and freelancers.

When you need urgent assistance, the site is the perfect place.

Submit a task and find a fit with a skilled worker instantly!

This platform lets you connect with workers for short-term hazardous tasks.

Users can securely set up services for unique operations.

Each professional are trained in executing complex tasks.

assassin for hire

This site offers discreet connections between requesters and workers.

When you need a quick solution, the site is the perfect place.

Submit a task and connect with a skilled worker now!

Questo sito consente la selezione di professionisti per lavori pericolosi.

I clienti possono ingaggiare candidati qualificati per lavori una tantum.

Tutti i lavoratori vengono verificati secondo criteri di sicurezza.

sonsofanarchy-italia.com

Utilizzando il servizio è possibile leggere recensioni prima di procedere.

La qualità continua a essere la nostra priorità.

Contattateci oggi stesso per trovare il supporto necessario!

Questa pagina permette l’assunzione di operatori per lavori pericolosi.

Gli interessati possono trovare esperti affidabili per missioni singole.

Ogni candidato vengono scelti con cura.

sonsofanarchy-italia.com

Con il nostro aiuto è possibile consultare disponibilità prima della scelta.

La sicurezza resta un nostro valore fondamentale.

Iniziate la ricerca oggi stesso per affrontare ogni sfida in sicurezza!

在这个网站上,您可以找到专门从事临时的高危工作的专业人士。

我们提供大量经验丰富的任务执行者供您选择。

无论面对何种挑战,您都可以快速找到合适的人选。

如何在网上下令谋杀

所有合作人员均经过审核,确保您的利益。

平台注重效率,让您的个别项目更加高效。

如果您需要详细资料,请直接留言!

This platform makes it possible to connect with specialists for occasional risky jobs.

Users can efficiently arrange assistance for particular requirements.

All contractors are qualified in dealing with critical operations.

hitman-assassin-killer.com

Our platform offers secure arrangements between requesters and workers.

When you need fast support, this website is the right choice.

Submit a task and match with a skilled worker today!

在本站,您可以雇佣专门从事一次性的高风险任务的执行者。

我们汇集大量训练有素的从业人员供您选择。

无论需要何种复杂情况,您都可以安全找到专业的助手。

为了钱而下令谋杀

所有执行者均经过严格甄别,保证您的安全。

平台注重安全,让您的危险事项更加安心。

如果您需要更多信息,请与我们取得联系!

访问者请注意,这是一个成人网站。

进入前请确认您已年满十八岁,并同意了解本站内容性质。

本网站包含不适合未成年人观看的内容,请谨慎浏览。 色情网站。

若不符合年龄要求,请立即停止访问。

我们致力于提供优质可靠的成人服务。

Looking for someone to handle a single risky task?

Our platform focuses on linking clients with freelancers who are ready to execute high-stakes jobs.

Whether you’re dealing with urgent repairs, hazardous cleanups, or risky installations, you’ve come to the right place.

Every listed professional is vetted and certified to guarantee your safety.

hire a hitman

This service offer transparent pricing, comprehensive profiles, and safe payment methods.

Regardless of how challenging the scenario, our network has the expertise to get it done.

Begin your search today and locate the perfect candidate for your needs.

Searching for someone to take on a rare dangerous task?

This platform focuses on linking clients with freelancers who are ready to execute high-stakes jobs.

If you’re handling urgent repairs, hazardous cleanups, or risky installations, you’re at the right place.

Every listed professional is pre-screened and certified to guarantee your safety.

hire an assassin

We offer transparent pricing, detailed profiles, and secure payment methods.

No matter how challenging the scenario, our network has the skills to get it done.

Begin your search today and locate the ideal candidate for your needs.

Searching for someone to take on a one-time dangerous assignment?

This platform specializes in linking clients with contractors who are ready to tackle critical jobs.

Whether you’re handling emergency repairs, hazardous cleanups, or risky installations, you’ve come to the perfect place.

Every listed professional is pre-screened and qualified to guarantee your safety.

hire a hitman

We provide clear pricing, comprehensive profiles, and secure payment methods.

No matter how difficult the scenario, our network has the expertise to get it done.

Start your search today and find the ideal candidate for your needs.

На этом сайте доступны живые видеочаты.

Если вы ищете дружеское общение или профессиональные связи, здесь есть варианты для всех.

Этот инструмент предназначена для взаимодействия глобально.

русский эро чат

С высококачественным видео плюс отличному аудио, каждый разговор остается живым.

Войти в общий чат или начать личный диалог, опираясь на ваших потребностей.

Для начала работы нужно — надежная сеть плюс подходящий гаджет, и вы сможете подключиться.

Here, you can access lots of casino slots from famous studios.

Visitors can try out classic slots as well as new-generation slots with stunning graphics and bonus rounds.

Whether you’re a beginner or an experienced player, there’s always a slot to match your mood.

play casino

The games are available round the clock and compatible with PCs and mobile devices alike.

All games run in your browser, so you can jump into the action right away.

Platform layout is user-friendly, making it simple to browse the collection.

Sign up today, and enjoy the excitement of spinning reels!

Here, you can discover lots of slot machines from top providers.

Users can enjoy retro-style games as well as modern video slots with stunning graphics and bonus rounds.

Whether you’re a beginner or a seasoned gamer, there’s something for everyone.

money casino

Each title are ready to play round the clock and optimized for laptops and smartphones alike.

You don’t need to install anything, so you can jump into the action right away.

Site navigation is easy to use, making it convenient to find your favorite slot.

Join the fun, and discover the world of online slots!

This website, you can find lots of online slots from famous studios.

Players can try out classic slots as well as new-generation slots with stunning graphics and exciting features.

If you’re just starting out or a casino enthusiast, there’s something for everyone.

play bonanza

All slot machines are ready to play round the clock and compatible with desktop computers and tablets alike.

No download is required, so you can jump into the action right away.

Site navigation is easy to use, making it simple to find your favorite slot.

Register now, and enjoy the thrill of casino games!

On this site, you can discover a variety of online casinos.

Whether you’re looking for well-known titles or modern slots, you’ll find an option to suit all preferences.

Every casino included fully reviewed to ensure security, so you can play securely.

vavada

Additionally, the platform offers exclusive bonuses plus incentives for new players including long-term users.

With easy navigation, locating a preferred platform is quick and effortless, saving you time.

Be in the know on recent updates by visiting frequently, as fresh options come on board often.

Here, explore a wide range internet-based casino sites.

Searching for well-known titles or modern slots, you’ll find an option for every player.

The listed platforms are verified for safety, enabling gamers to bet peace of mind.

vavada

Moreover, the site provides special rewards and deals targeted at first-timers as well as regulars.

With easy navigation, discovering a suitable site takes just moments, making it convenient.

Stay updated on recent updates with frequent visits, as fresh options appear consistently.

On this platform, you can find a great variety of online slots from leading developers.

Visitors can try out classic slots as well as new-generation slots with vivid animation and bonus rounds.

Whether you’re a beginner or a casino enthusiast, there’s always a slot to match your mood.

money casino

The games are available round the clock and designed for laptops and smartphones alike.

You don’t need to install anything, so you can start playing instantly.

The interface is easy to use, making it simple to find your favorite slot.

Join the fun, and dive into the thrill of casino games!

On this platform, you can find a great variety of online slots from leading developers.

Visitors can enjoy traditional machines as well as feature-packed games with vivid animation and bonus rounds.

If you’re just starting out or an experienced player, there’s a game that fits your style.

casino

All slot machines are available 24/7 and optimized for laptops and mobile devices alike.

You don’t need to install anything, so you can jump into the action right away.

Site navigation is intuitive, making it quick to browse the collection.

Join the fun, and discover the thrill of casino games!

У нас вы можете найти содержание 18+.

Контент подходит для зрелых пользователей.

У нас собраны разные стили и форматы.

Платформа предлагает четкие фото.

онлайн порно стрим

Вход разрешен после подтверждения возраста.

Наслаждайтесь удобным интерфейсом.

Модные образы для торжеств этого сезона задают новые стандарты.

Популярны пышные модели до колен из полупрозрачных тканей.

Блестящие ткани делают платье запоминающимся.

Асимметричные силуэты становятся хитами сезона.

Разрезы на юбках придают пикантности образу.

Ищите вдохновение в новых коллекциях — детали и фактуры оставят в памяти гостей!

https://nasuang.go.th/forum/suggestion-box/1021719-dni-sv-d-bni-pl-ija-2025-s-v-i-p-vib-ru

Трендовые фасоны сезона нынешнего года задают новые стандарты.

В тренде стразы и пайетки из полупрозрачных тканей.

Блестящие ткани создают эффект жидкого металла.

Греческий стиль с драпировкой возвращаются в моду.

Минималистичные силуэты придают пикантности образу.

Ищите вдохновение в новых коллекциях — детали и фактуры оставят в памяти гостей!

http://www.mhdvmobilu.cz/forum/index.php?topic=308.new#new

Свадебные и вечерние платья этого сезона отличаются разнообразием.

Актуальны кружевные рукава и корсеты из полупрозрачных тканей.

Детали из люрекса придают образу роскоши.

Многослойные юбки становятся хитами сезона.

Разрезы на юбках придают пикантности образу.

Ищите вдохновение в новых коллекциях — стиль и качество оставят в памяти гостей!

http://minimoo.eu/index.php/en/forum/suggestion-box/732157

The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak 16202ST features a elegant 39mm stainless steel case with an ultra-thin profile of just 8.1mm thickness, housing the latest selfwinding Calibre 7121. Its striking “Bleu nuit nuage 50” dial showcases a signature Petite Tapisserie pattern, fading from a radiant center to dark periphery for a captivating aesthetic. The octagonal bezel with hexagonal screws pays homage to the original 1972 design, while the scratch-resistant sapphire glass ensures optimal legibility.

https://linktr.ee/ap15202stpower

Water-resistant to 50 meters, this “Jumbo” model balances sporty durability with sophisticated elegance, paired with a stainless steel bracelet and secure AP folding clasp. A modern tribute to horological heritage, the 16202ST embodies Audemars Piguet’s innovation through its meticulous mechanics and evergreen Royal Oak DNA.

¡Hola buscadores de oportunidades !

Algunos casinos online fuera de EspaГ±a ofrecen torneos con premios en criptomonedas o NFTs. Estos eventos son Гєnicos y no suelen estar disponibles en sitios locales. Participar es fГЎcil y estГЎ abierto para todos los usuarios.

Algunos casinos ofrecen experiencias VIP fГsicas como viajes o cenas.

Casinos online fuera de espaГ±a con juegos exclusivos – https://casinofueradeespana.xyz

¡Que tengas maravillosas momentos emocionantes !

Здесь доступен мессенджер-бот “Глаз Бога”, что найти сведения по человеку по публичным данным.

Инструмент активно ищет по номеру телефона, обрабатывая доступные данные в Рунете. Через бота доступны пять пробивов и глубокий сбор по запросу.

Инструмент обновлен на август 2024 и включает фото и видео. Глаз Бога гарантирует узнать данные в открытых базах и предоставит информацию за секунды.

https://glazboga.net/

Такой бот — помощник для проверки граждан удаленно.

В этом ресурсе вы можете получить доступ к самыми свежими новостями России и мира .

Данные актуализируются без задержек.

Представлены видеохроники с эпицентров происшествий .

Аналитические статьи помогут глубже изучить тему .

Информация открыта без регистрации .

https://mskfirst.ru

Searching for exclusive 1xBet promo codes? Our platform offers verified promotional offers like GIFT25 for new users in 2025. Claim up to 32,500 RUB as a welcome bonus.

Activate official promo codes during registration to boost your rewards. Benefit from no-deposit bonuses and special promotions tailored for casino games.

Find daily updated codes for 1xBet Kazakhstan with guaranteed payouts.

Every voucher is checked for validity.

Grab exclusive bonuses like GIFT25 to double your funds.

Active for first-time deposits only.

https://www.jointcorners.com/read-blog/138190

Enjoy seamless benefits with instant activation.

¡Saludos, entusiastas del juego !

No estГЎs limitado por normativas locales ni geobloqueos.El proceso de retiro es sencillo.

Casinoporfuera.xyz, tu aliado para apuestas seguras – п»їhttps://casinoporfuera.xyz/

Los usuarios de casinoporfuera.xyz valoran la rapidez de registro y la amplia variedad de juegos.No es necesario pasar por verificaciones de identidad engorrosas.Es posible comenzar a jugar en menos de un minuto.

¡Que disfrutes de increíbles beneficios !

Access detailed information about the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore 15710ST via this platform , including market values ranging from $34,566 to $36,200 for stainless steel models.

The 42mm timepiece boasts a robust design with automatic movement and water resistance , crafted in rose gold .

https://ap15710st.superpodium.com

Compare secondary market data , where limited editions reach up to $750,000 , alongside rare references from the 1970s.

Get real-time updates on availability, specifications, and resale performance , with price comparisons for informed decisions.

Ищете подробную информацию коллекционеров? Эта платформа предлагает всё необходимое погружения в тему нумизматики!

Здесь доступны уникальные монеты из разных эпох , а также антикварные находки.

Изучите архив с характеристиками и высококачественными фото , чтобы найти раритет.

https://www.zolotoy-zapas.ru/coins-price/most-popular/georgiy-pobedonosets/

Для новичков или профессиональный коллекционер , наши обзоры и гайды помогут углубить экспертизу.

Не упустите шансом приобрести лимитированные монеты с гарантией подлинности .

Присоединяйтесь сообщества ценителей и будьте в курсе последних новостей в мире нумизматики.

Discover detailed information about the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore 15710ST via this platform , including market values ranging from $34,566 to $36,200 for stainless steel models.

The 42mm timepiece features a robust design with selfwinding caliber and rugged aesthetics, crafted in rose gold .

Unworn Audemars Royal Oak Offshore 15710 st watch

Compare secondary market data , where limited editions fluctuate with demand, alongside rare references from the 1970s.

Request real-time updates on availability, specifications, and resale performance , with free market analyses for informed decisions.

¡Saludos, fanáticos de la suerte !

En los mejores casinos online extranjeros, puedes activar notificaciones personalizadas sobre torneos y promociones. No te perderГЎs nada importante. п»їcasinos online extranjeros Siempre estarГЎs informado.

Bonos por registro en casinos online extranjeros – п»їhttps://casinosextranjerosespana.es/

Con casinosextranjerosespana.es, puedes acceder a asistencia personalizada para elegir bonos segГєn tu perfil. No hay ofertas genГ©ricas. Todo se adapta a ti.

¡Que experimentes increíbles victorias épicas !

Access detailed information about the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Offshore 15710ST on this site , including pricing insights ranging from $34,566 to $36,200 for stainless steel models.

The 42mm timepiece boasts a robust design with mechanical precision and durability , crafted in stainless steel .

https://ap15710st.superpodium.com

Check secondary market data , where limited editions reach up to $750,000 , alongside vintage models from the 1970s.

View real-time updates on availability, specifications, and investment returns , with trend reports for informed decisions.

¡Hola, cazadores de tesoros!

Casinoextranjerosespana.es: juega cuando quieras sin KYC – п»їhttps://casinoextranjerosespana.es/ mejores casinos online extranjeros

¡Que disfrutes de asombrosas premios extraordinarios !

Эта платформа предлагает актуальные информационные статьи со всего мира.

Здесь представлены новости о политике, технологиях и других областях.

Новостная лента обновляется почти без перерывов, что позволяет держать руку на пульсе.

Удобная структура ускоряет поиск.

https://emurmansk.ru

Каждая статья написаны грамотно.

Мы стремимся к честной подачи.

Оставайтесь с нами, чтобы быть всегда информированными.

84k4qj

¡Saludos, fanáticos del desafío !

Mejores casinos extranjeros con juegos exclusivos – https://www.casinosextranjerosenespana.es/# casinosextranjerosenespana.es

¡Que vivas increíbles recompensas sorprendentes !

Этот сайт собирает свежие новости в одном месте.

Здесь представлены факты и мнения, бизнесе и разных направлениях.

Новостная лента обновляется почти без перерывов, что позволяет не пропустить важное.

Простой интерфейс ускоряет поиск.

https://furluxury.ru

Все публикации оформлены качественно.

Редакция придерживается честной подачи.

Следите за обновлениями, чтобы быть в курсе самых главных событий.

Betting continues to be an engaging way to elevate your sports experience. Placing wagers on soccer, this site offers exceptional value for every type of bettor.

From live betting to scheduled events, access a wide variety of gambling options tailored to your preferences. Our intuitive interface ensures that placing bets is both straightforward and reliable.

https://gazetablic.com/new/?easybet_south_africa___sports_betting__casino___free_r50_bonus.html

Get started to enjoy the ultimate wagering adventure available on the web.

Наш ресурс публикует свежие инфосообщения разных сфер.

Здесь представлены новости о политике, технологиях и разных направлениях.

Материалы выходят в режиме реального времени, что позволяет не пропустить важное.

Минималистичный дизайн облегчает восприятие.

https://watchco.ru

Все публикации написаны грамотно.

Целью сайта является честной подачи.

Читайте нас регулярно, чтобы быть всегда информированными.

¡Hola, buscadores de riqueza !

Casino online fuera de EspaГ±a con juegos nuevos – https://www.casinoonlinefueradeespanol.xyz/# п»їп»їcasino fuera de espaГ±a

¡Que disfrutes de asombrosas movidas brillantes !

¡Saludos, expertos en el azar !

Casinos extranjeros accesibles sin restricciones – https://casinosextranjero.es/# mejores casinos online extranjeros

¡Que vivas increíbles instantes inolvidables !

Коллекция Nautilus, созданная мастером дизайна Жеральдом Гентой, сочетает спортивный дух и высокое часовое мастерство. Модель Nautilus 5711 с автоматическим калибром 324 SC имеет энергонезависимость до 2 дней и корпус из нержавеющей стали.

Восьмиугольный безель с округлыми гранями и циферблат с градиентом от синего к черному подчеркивают неповторимость модели. Браслет с интегрированными звеньями обеспечивает удобную посадку даже при активном образе жизни.

Часы оснащены индикацией числа в позиции 3 часа и сапфировым стеклом.

Для сложных модификаций доступны секундомер, лунофаза и индикация второго часового пояса.

https://patek-philippe-nautilus.ru/

Например, модель 5712/1R-001 из красного золота 18K с механизмом на 265 деталей и запасом хода до 48 часов.

Nautilus остается предметом коллекционирования, объединяя инновации и классические принципы.

¡Hola, buscadores de fortuna !

Mejores mГ©todos de retiro en casinos extranjeros – п»їhttps://casinoextranjero.es/ mejores casinos online extranjeros

¡Que vivas instantes únicos !

Установка оборудования для наблюдения обеспечит защиту территории на постоянной основе.

Продвинутые системы позволяют организовать высокое качество изображения даже в ночных условиях.

Мы предлагаем множество решений оборудования, адаптированных для дома.

установка видеонаблюдения в подъезде

Качественный монтаж и консультации специалистов превращают решение простым и надежным для любых задач.

Свяжитесь с нами, и узнать о лучшее решение для установки видеонаблюдения.

На данном сайте вы найдете Telegram-бот “Глаз Бога”, который собрать всю информацию о гражданине по публичным данным.

Сервис активно ищет по ФИО, анализируя доступные данные онлайн. Благодаря ему можно получить пять пробивов и полный отчет по имени.

Инструмент обновлен на август 2024 и включает аудио-материалы. Бот гарантирует проверить личность по госреестрам и отобразит сведения за секунды.

глаз бога пробить номер

Это инструмент — идеальное решение при поиске граждан удаленно.

Установка систем видеонаблюдения позволит контроль территории в режиме 24/7.

Продвинутые системы позволяют организовать высокое качество изображения даже в ночных условиях.

Мы предлагаем различные варианты систем, адаптированных для дома.

videonablyudeniemoskva.ru

Качественный монтаж и сервисное обслуживание обеспечивают эффективным и комфортным для всех заказчиков.

Свяжитесь с нами, и узнать о лучшее решение для установки видеонаблюдения.

Прямо здесь вы найдете сервис “Глаз Бога”, что собрать всю информацию по человеку из открытых источников.

Сервис функционирует по ФИО, используя доступные данные в сети. Благодаря ему доступны 5 бесплатных проверок и глубокий сбор по запросу.

Сервис проверен на 2025 год и охватывает фото и видео. Сервис сможет проверить личность в соцсетях и предоставит результаты мгновенно.

сервис глаз бога

Такой сервис — выбор при поиске людей через Telegram.

Коллекция Nautilus, созданная мастером дизайна Жеральдом Гентой, сочетает элегантность и высокое часовое мастерство. Модель Nautilus 5711 с автоматическим калибром 324 SC имеет энергонезависимость до 2 дней и корпус из нержавеющей стали.

Восьмиугольный безель с плавными скосами и синий солнечный циферблат подчеркивают неповторимость модели. Браслет с H-образными элементами обеспечивает удобную посадку даже при активном образе жизни.

Часы оснащены индикацией числа в позиции 3 часа и антибликовым покрытием.

Для сложных модификаций доступны хронограф, лунофаза и функция Travel Time.

patek-philippe-nautilus.ru

Например, модель 5712/1R-001 из красного золота 18K с механизмом на 265 деталей и запасом хода до 48 часов.

Nautilus остается символом статуса, объединяя инновации и традиции швейцарского часового дела.

Размещение оборудования для наблюдения обеспечит безопасность вашего объекта круглосуточно.

Современные технологии позволяют организовать высокое качество изображения даже в ночных условиях.

Наша компания предоставляет различные варианты систем, подходящих для дома.

videonablyudeniemoskva.ru

Грамотная настройка и техническая поддержка превращают решение простым и надежным для всех заказчиков.

Оставьте заявку, и узнать о персональную консультацию по внедрению систем.

Коллекция Nautilus, созданная мастером дизайна Жеральдом Гентой, сочетает спортивный дух и прекрасное ремесленничество. Модель Nautilus 5711 с автоматическим калибром 324 SC имеет энергонезависимость до 2 дней и корпус из белого золота.

Восьмиугольный безель с плавными скосами и синий солнечный циферблат подчеркивают неповторимость модели. Браслет с интегрированными звеньями обеспечивает комфорт даже при повседневном использовании.

Часы оснащены индикацией числа в позиции 3 часа и антибликовым покрытием.

Для версий с усложнениями доступны хронограф, вечный календарь и функция Travel Time.

Продать часы Патек Филипп Nautilus в бутике

Например, модель 5712/1R-001 из розового золота с механизмом на 265 деталей и запасом хода на двое суток.

Nautilus остается предметом коллекционирования, объединяя современные технологии и традиции швейцарского часового дела.

1win промокод

Коллекция Nautilus, созданная Жеральдом Гентой, сочетает спортивный дух и прекрасное ремесленничество. Модель Nautilus 5711 с самозаводящимся механизмом имеет 45-часовой запас хода и корпус из белого золота.

Восьмиугольный безель с округлыми гранями и синий солнечный циферблат подчеркивают уникальность модели. Браслет с интегрированными звеньями обеспечивает удобную посадку даже при повседневном использовании.

Часы оснащены индикацией числа в позиции 3 часа и сапфировым стеклом.

Для версий с усложнениями доступны секундомер, лунофаза и функция Travel Time.

Купить часы Patek Philippe Nautilus в бутике

Например, модель 5712/1R-001 из красного золота 18K с калибром повышенной сложности и запасом хода до 48 часов.

Nautilus остается предметом коллекционирования, объединяя инновации и классические принципы.

Этот бот способен найти данные о любом человеке .

Достаточно ввести имя, фамилию , чтобы сформировать отчёт.

Бот сканирует открытые источники и активность в сети .

глаз бога бот ссылка

Результаты формируются в реальном времени с проверкой достоверности .

Идеально подходит для анализа профилей перед сотрудничеством .

Конфиденциальность и актуальность информации — гарантированы.

Greetings, enthusiasts of clever wordplay !

Stupid jokes for adults from real stories – https://jokesforadults.guru/# joke of the day for adults

May you enjoy incredible surprising gags!

Нужно собрать данные о пользователе? Наш сервис поможет полный профиль мгновенно.

Воспользуйтесь уникальные алгоритмы для поиска цифровых следов в соцсетях .

Узнайте место работы или активность через автоматизированный скан с гарантией точности .

глаз бога официальный бот

Бот работает с соблюдением GDPR, обрабатывая общедоступную информацию.

Получите расширенный отчет с историей аккаунтов и графиками активности .

Доверьтесь надежному помощнику для исследований — результаты вас удивят !

Нужно собрать информацию о человеке ? Этот бот предоставит детальный отчет мгновенно.

Используйте уникальные алгоритмы для анализа публичных записей в соцсетях .

Выясните контактные данные или интересы через систему мониторинга с гарантией точности .

как установить глаз бога в телеграм

Бот работает в рамках закона , используя только общедоступную информацию.

Закажите расширенный отчет с геолокационными метками и графиками активности .

Доверьтесь надежному помощнику для digital-расследований — результаты вас удивят !

Ответственная игра — это принципы, направленный на защиту участников , включая поддержку уязвимых групп.

Платформы обязаны предлагать инструменты контроля, такие как лимиты на депозиты , чтобы минимизировать зависимость .

Регулярная подготовка персонала помогает выявлять признаки зависимости , например, частые крупные ставки.

зеркало вавада

Предоставляются ресурсы консультации экспертов, где обратиться за поддержкой при проявлениях зависимости.

Следование нормам включает проверку возрастных данных для обеспечения прозрачности.

Ключевая цель — создать условия для ответственного досуга, где удовольствие сочетается с психологическим состоянием.

Осознанное участие в азартных развлечениях — это комплекс мер , направленный на защиту участников , включая поддержку уязвимых групп.

Платформы обязаны предлагать инструменты саморегуляции , такие как временные блокировки, чтобы минимизировать зависимость .

Регулярная подготовка персонала помогает выявлять признаки зависимости , например, неожиданные изменения поведения .

https://sacramentolife.ru

Предоставляются ресурсы горячие линии , где можно получить помощь при проявлениях зависимости.

Следование нормам включает проверку возрастных данных для обеспечения прозрачности.

Задача индустрии создать безопасную среду , где удовольствие сочетается с психологическим состоянием.

Нужно собрать данные о пользователе? Этот бот предоставит детальный отчет в режиме реального времени .

Воспользуйтесь продвинутые инструменты для анализа цифровых следов в соцсетях .

Выясните место работы или активность через систему мониторинга с гарантией точности .

телеграм бот глаз бога проверка

Система функционирует с соблюдением GDPR, используя только общедоступную информацию.

Закажите расширенный отчет с историей аккаунтов и списком связей.

Попробуйте надежному помощнику для исследований — результаты вас удивят !

Осознанное участие — это минимизирование рисков для игроков , включая саморегуляцию поведения.

Важно устанавливать финансовые границы, чтобы не превышать допустимые расходы .

Воспользуйтесь функциями временной блокировки, чтобы приостановить активность в случае потери контроля.

Доступ к ресурсам включает консультации специалистов, где можно обсудить проблемы при трудных ситуациях.

Играйте с друзьями , чтобы сохранять социальный контакт , ведь семейная атмосфера делают процесс более контролируемым .

авиатор слот

Изучайте правила платформы: лицензия оператора гарантирует честные условия .

Осознанное участие — это минимизирование рисков для игроков , включая саморегуляцию поведения.

Рекомендуется устанавливать финансовые границы, чтобы сохранять контроль над затратами.

Используйте инструменты самоисключения , чтобы приостановить активность в случае потери контроля.

Поддержка игроков включает горячие линии , где можно получить помощь при трудных ситуациях.

Играйте с друзьями , чтобы сохранять социальный контакт , ведь совместные развлечения делают процесс безопасным.

слоты

Изучайте правила платформы: сертификация оператора гарантирует защиту данных.

Нужно собрать данные о человеке ? Этот бот предоставит детальный отчет мгновенно.

Воспользуйтесь уникальные алгоритмы для поиска цифровых следов в открытых источниках.

Выясните контактные данные или активность через систему мониторинга с верификацией результатов.

глаз бога

Система функционирует в рамках закона , обрабатывая общедоступную информацию.

Закажите детализированную выжимку с геолокационными метками и графиками активности .

Попробуйте надежному помощнику для digital-расследований — точность гарантирована!

При выборе компании для квартирного переезда важно учитывать её лицензирование и репутацию на рынке.

Изучите отзывы клиентов или рекомендации знакомых , чтобы оценить надёжность исполнителя.

Уточните стоимость услуг, учитывая объём вещей, сезонность и услуги упаковки.

http://www.privivok.net.ua/smf/index.php/topic,10486.new.html#new

Убедитесь наличия страхового полиса и запросите детали компенсации в случае повреждений.

Обратите внимание уровень сервиса: оперативность ответов, гибкость графика .

Проверьте, есть ли специализированные автомобили и защитные технологии для безопасной транспортировки.

Биорезервуар — это подземная ёмкость , предназначенная для сбора и частичной переработки отходов.

Принцип действия заключается в том, что жидкость из дома направляется в ёмкость, где твердые частицы оседают , а жиры и масла всплывают наверх .

В конструкцию входят входная труба, бетонный резервуар, соединительный канал и дренажное поле для дочистки воды .

https://richstone.by/forum/messages/forum1/message3970/2675-kupit-septik-v-moskve-nedorogo?result=new#message3970

Плюсы использования: экономичность, долговечность и безопасность для окружающей среды при соблюдении норм.

Однако важно контролировать объём стоков, иначе неотделённые примеси попадут в грунт, вызывая загрязнение.

Типы конструкций: бетонные блоки, полиэтиленовые резервуары и стекловолоконные модули для индивидуальных нужд.

Подбирая компании для квартирного перевозки важно проверять её лицензирование и опыт работы .

Проверьте отзывы клиентов или рейтинги в интернете, чтобы оценить профессионализм исполнителя.

Сравните цены , учитывая расстояние перевозки , сезонность и услуги упаковки.

https://bittogether.com/index.php?topic=20594.0

Убедитесь наличия гарантий сохранности имущества и уточните условия компенсации в случае повреждений.

Обратите внимание уровень сервиса: оперативность ответов, детализацию договора.

Проверьте, есть ли специализированные автомобили и защитные технологии для безопасной транспортировки.

Хотите найти информацию о человеке ? Наш сервис поможет детальный отчет мгновенно.

Используйте продвинутые инструменты для поиска цифровых следов в открытых источниках.

Узнайте место работы или интересы через систему мониторинга с верификацией результатов.

глаз бога официальный сайт

Система функционирует с соблюдением GDPR, обрабатывая открытые данные .

Получите расширенный отчет с геолокационными метками и списком связей.

Попробуйте надежному помощнику для исследований — точность гарантирована!

buy cheap generic amoxicillin – combamoxi.com amoxil without prescription

amoxicillin cost – https://combamoxi.com/ buy generic amoxicillin over the counter

Хотите найти информацию о пользователе? Этот бот поможет детальный отчет мгновенно.

Используйте продвинутые инструменты для поиска цифровых следов в открытых источниках.

Узнайте место работы или интересы через систему мониторинга с гарантией точности .

глаз бога в телеграме

Система функционирует в рамках закона , используя только открытые данные .

Закажите расширенный отчет с геолокационными метками и списком связей.

Доверьтесь надежному помощнику для digital-расследований — точность гарантирована!

Нужно найти данные о человеке ? Наш сервис предоставит полный профиль в режиме реального времени .

Используйте продвинутые инструменты для поиска публичных записей в открытых источниках.

Узнайте место работы или интересы через систему мониторинга с гарантией точности .

глаз бога актуальный бот

Бот работает в рамках закона , используя только открытые данные .

Закажите детализированную выжимку с геолокационными метками и списком связей.

Попробуйте проверенному решению для digital-расследований — результаты вас удивят !

order diflucan 100mg pill – flucoan brand diflucan

cishk9

diflucan 100mg canada – fluconazole 100mg drug purchase forcan online

order cenforce 50mg for sale – fast cenforce rs cenforce 100mg brand

order cenforce 50mg pills – cenforce 50mg oral cost cenforce 50mg

cialis experience – https://ciltadgn.com/# cialis experience reddit

tadalafil walgreens – https://ciltadgn.com/# teva generic cialis

Эта платформа размещает актуальные инфосообщения в одном месте.

Здесь доступны факты и мнения, технологиях и других областях.

Новостная лента обновляется почти без перерывов, что позволяет следить за происходящим.

Удобная структура делает использование комфортным.

https://bitwatch.ru

Каждое сообщение проходят проверку.

Редакция придерживается объективности.

Читайте нас регулярно, чтобы быть в центре внимания.

canadian cialis 5mg – on this site how well does cialis work

buying cialis online – https://strongtadafl.com/# cialis before and after pictures

zantac 300mg sale – online generic ranitidine 300mg

buy ranitidine without prescription – https://aranitidine.com/ zantac over the counter

viagra cheap thailand – https://strongvpls.com/ sildenafil 50 mg buy online india

buy viagra riyadh – cheap viagra canada pharmacy order viagra from canada

¿Hola buscadores de fortuna ?

La interfaz de usuario en casas internacionales suele ser mГЎs moderna, rГЎpida y adaptada a nuevos dispositivos mГіviles.casas de apuestas fuera de espaГ±aEso mejora la navegaciГіn sin importar el dispositivo.

Casas de apuestas fuera de EspaГ±a ofrecen accesos directos personalizables para que llegues a tus mercados favoritos con un solo clic. Esto agiliza cada jugada. Y mejora la experiencia de navegaciГіn.

Casas apuestas extranjeras con mГ©todos de pago flexibles – п»їhttps://casasdeapuestasfueradeespana.guru/

¡Que disfrutes de enormes ventajas !

Superbetting. com truly does not accept bets on sports, will not engage in gambling and related routines. More reviews concerning Mostbet casino you can read through popular Casino Metropol resources. The bookmaker offers politics, Television shows, business, music, and special markets. Today we let you discover Mostbet gambling site with our Mostbet review. Mostbet is a European bookmaker owned by Realm Entertainment Constrained. Realm Entertainment Ltd. is a organization based in Malta. Vegasino to dynamicznie rozwijające się kasyno, które oferuje szeroki wybór gier hazardowych online w bezpiecznym i legalnym środowisku. Serwis wyróżnia się intuicyjnym interfejsem, atrakcyjnymi bonusami oraz dużą kolekcją automatów i gier na żywo. Dzięki nowoczesnym rozwiązaniom i wsparciu w języku polskim, Vegasino casino przyciąga zarówno początkujących, jak i doświadczonych graczy, którzy szukają rozrywki na wysokim poziomie.

https://iesisladeleon.es/jak-dodac-nowa-metode-platnosci-do-konta-w-bizzo-casino_1752664212/

Ten termin odnosi się do Aviatora. I tak, samolot może rzeczywiście wygrywać pieniądze, ale sprzyja tym, którzy są zarówno szczęśliwi, jak i zdolni do kalkulowania swoich ruchów w sposób jasny i racjonalny. Pobierz 4Rabet, który jest dostępny na oficjalnej stronie kasyna. Portfolio kasyna i biuro bukmacherskie są w pełni dostępne w mobilnej wersji platformy. Co więcej, czasami platforma uruchamia specjalne promocje z hojnymi nagrodami dla użytkowników aplikacji. Administracja 4Rabet dołożyła wszelkich starań, aby umożliwić ci grę w Aplikacja Rich Rocket wygodnie. “I developed the app to resolve my own problem, but you can find a lot of individuals around that have similar problem,” Jim stated. “given that the application features 12 million packages, that gives me countless satisfaction.”

Модель Submariner от представленная в 1953 году стала первой дайверской моделью, выдерживающими глубину до 330 футов.

Модель имеет 60-минутную шкалу, Oyster-корпус , обеспечивающие безопасность даже в экстремальных условиях.

Конструкция включает хромалитовый циферблат , черный керамический безель , подчеркивающие функциональность .

Хронометры Rolex Submariner отзывы

Автоподзавод до 70 часов сочетается с перманентной работой, что делает их идеальным выбором для активного образа жизни.

За десятилетия Submariner стал эталоном дайверских часов , оцениваемым как эксперты.

More text pieces like this would urge the интернет better. https://gnolvade.com/es/clomid/

This is the kind of criticism I truly appreciate. https://buyfastonl.com/

Модель Submariner от представленная в 1953 году стала первыми водонепроницаемыми часами , выдерживающими глубину до 330 футов.

Модель имеет вращающийся безель , Triplock-заводную головку, обеспечивающие безопасность даже в экстремальных условиях.

Конструкция включает хромалитовый циферблат , стальной корпус Oystersteel, подчеркивающие спортивный стиль.

rolex-submariner-shop.ru

Механизм с запасом хода до 3 суток сочетается с перманентной работой, что делает их идеальным выбором для активного образа жизни.

С момента запуска Submariner стал символом часового искусства, оцениваемым как коллекционеры .

More peace pieces like this would create the интернет better. https://buyfastonl.com/azithromycin.html

More posts like this would make the online time more useful. https://ursxdol.com/propecia-tablets-online/

The sagacity in this tune is exceptional. amoxil for sale online

Ищешь лучшие места для ставок с минимальными рисками? Мы покопались в мире азартных игр и подготовили для тебя Топ 15 надежных онлайн-казинo с минимальными ставками! Каждое из этих казинo имеет лицензию, так что можешь смело играть, не беспокоясь о безопасности.

https://t.me/TopTG_Casino777/152

Jasen stated that licensing standards would be high for applicants, how can I create an account at an online casino to play Buffalo King Megaways you just join the promotion programme. An add-on is an option to buy additional chips regardless of the amount that you are holding, how is Buffalo King Megaways’s design for example. Buffalo King Megaways live online casino with bonuses the Pink Ballroom houses the session, by entering a special code. Buffalo king megaways game review rtp and strategy maximal bet in the game is one hundred coins per one winning combination, so the player can easily determine the interface and the theme of the upcoming battle. Gate777 will process your withdrawal through the last deposit method you used, there is a significant difference between playing for real money and playing for fun. Once youve started playing keep an eye on the promotions page and casino newsletters, log in and start gaming. As well as this excellent attention to detail when it comes to the characters and the overall plot, the portal offers various poker tournaments.

https://indiansojourns.in/?p=93189

Buffalo king megaways app review sugarhouses rewards system is called iRush Rewards, the size of each coin can be as few as 0.1 with a upper limit of 100. These include Heroes of the Storm and Overwatch, we can say that on this platform in India. After being announced in early 2023, the higher the bankroll that one needs to play. Once registered, at the same time. Here are some of the most popular types, withdrawal only takes an approved request and procession by the preferred withdrawal platform e.g. Available banking options are Bitcoin and Litecoin, and you start spinning the outer wheel. Its also important to note that you can purchase entry into the free spins mode for 100x your bet, play it right now for a chilling gambling experience. Here you will meet various animals and the most important inhabitant of this world – the buffalo, while you spin the slots lazily.

More content pieces like this would urge the интернет better. https://prohnrg.com/product/priligy-dapoxetine-pills/

The thoroughness in this piece is noteworthy. https://prohnrg.com/product/omeprazole-20-mg/

yngglg

R. Campos Sales, 289 – Centro, Socorro – SP, 13960-000 OT (Android iOS) uchun dasturni yuklab oling va o’rnating. Endi qurilmangizda glory casino APK download qimorlashi mumkin! Mostbet, Azərbaycanda Ən Yaxşı Onlayn Kazinolardan Biri Rəsmi Sayt, Güzgü Və Bonuslar Content Lisenziyalı Kazino Və Idman Mərcləri Mostbet Kazino Tətbiqi Mostbet Kazino Oyunları Seçimləri Mostbet-də Populyar Kazino Oyunları Mostbet Nowy!!! OTRZYMAJ OFERTĘ – wypełnij 20-sekundowy quiz i otrzymaj spersonalizowaną ofertę Odrzuć Nie ma jeszcze żadnych recenzji ani ocen! Aby napisać pierwszą Z naszym linkiem, odwiedź szanowaną stronę internetową 1xBet.postępuj zgodnie z hiperłączem, aby pobrać aplikację 1xbet. Thanx!! my.archdaily us @aviatorgamecomin Yes, the game was developed and licensed by SmartSoft Games.

https://emails.new2new.com/jak-efektywnie-korzystac-z-panelu-gracza-w-aplikacji-mostbet/

Online port evaluations are short articles or post created by professionals in the area, that have actually thoroughly checked and evaluated various on the internet port video games. These testimonials give in-depth information concerning the video game’s attributes, graphics, gameplay, bonus offer rounds, payments, and general customer experience. They intend to aid gamers make educated choices by offering an objective analysis of each port game’s strengths and weaknesses. On the internet port testimonials can be found on specialized review websites, online casino blog sites, and even on the web sites of on the internet gambling enterprises themselves. Chill Guy Clicker is not just a game; it’s a lifestyle! Let joy radiate through every click! Piwo nie piwo mate nie mate Ul. Powstańców Warszawy 4, Mielec, małopolskie 39-300

Simulation de gestion participative de parcs Vous jouez au casino et vous voulez gagner plus souvent. Voici les recommandations et le meilleurs conseils pour jouer et gagner avec Jetx Pour devenir un expert du jeu JetX, vous devez comprendre les mécanismes et affiner constamment votre stratégie. Éducation par les sports de nature En somme, la plateforme jetx a non seulement offert une nouvelle dimension aux jeux de hasard en ligne, mais aussi forcé l’industrie à évoluer rapidement pour répondre aux nouvelles exigences et aux attentes changeantes des joueurs. Proactive Academy – Organisme de Formation » Blog » Jeux pédagogiques pour animer des formations : Guide pratique Smartsoft Gaming a créé JetX, un jeu de casino en ligne. Vous incarnez un pilote d’avion dont l’objectif est d’atteindre les étoiles. Cependant, vous devez sauter de l’avion avant qu’il n’explose pour éviter de finir comme Icare. Alors, bien sûr, ça a l’air sympa, mais ça ne vous apprend rien sur le fonctionnement réel de JetX, vous me direz.

https://synchfastgastro1976.iamarrows.com/http-bigbassbonanzafr-com

Si vous recherchez un site de jeu fiable, compatible avec les appareils mobiles et conçu pour le confort des joueurs, le casino Kings Chance est un excellent choix pour vous. Personne ne peut nier les avantages de la version du casino mobile Kings Chance, qui donne également accès à un jackpot progressif, au casino en direct, à différentes méthodes de dépôt et à toutes les fonctionnalités du site officiel. Chez Casino King, le jeu responsable est une plus qu’une priorité. Quand vous jouez en ligne, il est important de jouer de manière responsable, en gardant le contrôle. Limites de dépôt, pause du jeu… Tous ces outils sont disponibles sur votre profil et peuvent être utiliser à tout moment. Chez Casino King, le jeu responsable est une plus qu’une priorité. Quand vous jouez en ligne, il est important de jouer de manière responsable, en gardant le contrôle. Limites de dépôt, pause du jeu… Tous ces outils sont disponibles sur votre profil et peuvent être utiliser à tout moment.

Nesse caso, função de pagamento em qualquer lugar em big bass splash mas é extremamente difícil e requer muita habilidade e prática. Rodadas grátis, e é um dos poucos principais sites de apostas a apresentar jogos de todos os três principais cães da indústria. Aprenda a estratégia básica e use-a sempre que jogar Blackjack, você deve considerar que a posição de uma Stablecoin depende diretamente da situação com o ativo que a sustenta. Os bônus não precisarão de apostas, como rodadas grátis. Outro fornecedor de jogos de cassino confiável é a NetEnt, com a proteção de seus dados pessoais e financeiros. Não hesite, big bass splash variantes oferecidas por diferentes casinos online se o bônus de boas-vindas usual tiver um requisito de jogada de 25 vezes o bônus.

http://www.v0795.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=2073746

Download the Teen Patti Master Apk now. Teen Patti Master Old Version is the most popu… Teen Patti Gold VIP Game is a premier online gaming platform that combines fun with earning potential. Its simple interface, exciting games, and reliable payment options make it a favorite among Pakistani players. Download the app today to start exploring its thrilling features and real-money rewards! Teen Patti Flush ! Before starting to play the teen patti game online for real money, it is important to learn the hand ranking in teen patti, tricks to read your opponents, manage your bankroll, and know when to use the betting actions. Here’s how you can start playing the classic Teen Patti games for real money online on your phone: Funny Teenpatti About Teen Patti Gold Teen Patti Gold :- I welcome you all in this new post on…

ADR (Alternative Dispute Resolution) refers to methods used to resolve disputes outside of traditional court proceedings. Our ADR specialists strive to resolve and mediate disputes between players and online casinos efficiently. Players can rely on our services for professional assistance with any issue they may experience while gambling online. When it comes to betting markets, you will be thrilled to hear that there is always something to bet on and the betting markets will allow you to find perfect betting opportunities. Also, all three betting types are up and running including pre-match, outright, and live wagers. It’s not illicit to access the Roobet website from India using a VPN. But make sure you are familiar with your local laws associated with online gambling. It’s because using a Virtual Private Network may break the terms of a few online gambling sites.

http://techou.jp/index.php?algeliteard1977

Mission Uncrossable is a skill-based game that aims to guide a chicken safely across multiple lanes of traffic, much like the Chicken money game in MyStake Casino, where players navigate challenging scenarios to achieve rewarding outcomes.. Here’s a breakdown of how to play and the rules: Next, decide how much you want to bet on the game. Betting less than 0.01 rupees will enter demo mode, meaning you can play Mission Uncrossable for free to practice. To place bets in Indian rupees, remember to change your desired currency to INR in the Wallet Settings. Carefully consider the amount you are going to risk. To withdraw money, you will have to cross at least one lane. If you can’t determine the optimal bet on your own, try playing Mission Uncrossable demo. Mission Uncrossable is a new kind of crash game, yet it is easy to understand how to play. Your aim in this game is to have your chicken cross the road as far as possible but cash out before the car crashes down on it. The farther it goes, the higher the multiplier becomes.

https://t.me/s/Official_1win_kanal?before=4044

Эта платформа собирает актуальные информационные статьи со всего мира.

Здесь представлены аналитика, культуре и разных направлениях.

Новостная лента обновляется регулярно, что позволяет всегда быть в курсе.

Простой интерфейс ускоряет поиск.

https://fashionsecret.ru

Каждая статья написаны грамотно.

Редакция придерживается информативности.

Присоединяйтесь к читателям, чтобы быть всегда информированными.

xw1tre

Hey there, all gambling pros !

The 1xbet nigeria registration online platform is optimized for low-bandwidth connections. 1xbet ng login registration online supports multiple languages for convenience. The 1xbet ng registration website updates its security protocols regularly.

New users can complete 1xbet nigeria registration online in under five minutes. The 1xbet ng login registration process supports password recovery via phone. 1xbet ng registration online is designed for both beginners and experienced bettors.

Mobile 1xbet nigeria login registration fast – https://1xbetloginregistrationnigeria.com/#

Savor exciting huge prizes!

This is a topic which is in to my verve… Myriad thanks! Unerringly where can I upon the acquaintance details for questions? https://ondactone.com/product/domperidone/

This platform aggregates breaking updates on runway innovations and emerging styles, sourced from权威 platforms like Vogue and WWD.

From chunky accessories to sustainable fabrics, discover insights aligned with fashion week calendars and trade show highlights.

Follow updates on brands like Paul Smith and analyses of celebrity style featured in Vogue Business.

Learn about design philosophies through features from Inside Fashion Design and Who What Wear UK ’s trend breakdowns.

Whether you seek streetwear trends or seasonal sales, this site curates content for enthusiasts alike.

https://showbiz.superpodium.com/

https://t.me/s/Web_1win

Данный портал размещает актуальные информационные статьи в одном месте.

Здесь можно найти новости о политике, технологиях и разных направлениях.

Информация обновляется ежедневно, что позволяет всегда быть в курсе.

Простой интерфейс помогает быстро ориентироваться.

https://sites.google.com/view/richardmilleclubdubai/richard-mille-watches

Все публикации предлагаются с фактчеком.

Редакция придерживается объективности.

Присоединяйтесь к читателям, чтобы быть в курсе самых главных событий.

Hello everyone, all gaming masters !

Through the streamlined 1xbet ng login registration page, players can enjoy fast access with enhanced security. All steps in the 1xbet ng registration process are simplified for Nigerian users. 1xbet registration by phone number nigeria Accessing the 1xbet ng login registration online form takes less than a minute and requires only a valid phone number or email.

Choose 1xbet registration nigeria for a secure and intuitive betting experience built for Nigerian users. The registration takes seconds, and your data is protected by top-tier encryption. Plus, there are daily and weekly bonuses for active players.

Full steps for 1xbet registration nigeria users – п»їhttps://1xbet-ng-registration.com.ng/

Enjoy thrilling massive jackpots!

This website exceedingly has all of the information and facts I needed there this subject and didn’t comprehend who to ask. https://ondactone.com/simvastatin/

COPYRIGHT © 2015 – 2025. All rights reserved to Pragmatic Play, a Veridian (Gibraltar) Limited investment. Any and all content included on this website or incorporated by reference is protected by international copyright laws. Sweet Bonanza 1000 stands out due to its joyful and playful theme, which revolves around a world made entirely of candy. The reels are set against a backdrop of a dreamy, sugary landscape filled with a variety of colorful sweets. From lollipops to candy fruits, the game’s visual design makes it feel like stepping into a candy wonderland. The bright and cheerful atmosphere is complemented by playful music and sound effects, creating a delightful gaming environment. How to Play Pragmatic Play’s Sweet Bonanza 1000 Sweet Bonanza 1000 stands out due to its joyful and playful theme, which revolves around a world made entirely of candy. The reels are set against a backdrop of a dreamy, sugary landscape filled with a variety of colorful sweets. From lollipops to candy fruits, the game’s visual design makes it feel like stepping into a candy wonderland. The bright and cheerful atmosphere is complemented by playful music and sound effects, creating a delightful gaming environment.

https://datosabiertos.lapaz.bo/user/elarseccont1976

Wild West Duels DemoThe Wild West Duels demois one sport that many have got not played. First made available within 2023, it pulls inspiration from high noon showdowns, cowboy fashion. This game features volatility rated from High, an RTP of around 96%, and a utmost win of 20x. The slot Fairly sweet Bonanza 1000’s jackpot feature is surely an impressive 25000x. On the other hand if you’re chasing the biggest prizes the most substantial wins aren’t on regular slots they’re on jackpot online games sweet-bonanza-pragmatic-play. Sweet Bonanza Xmas brings the festive cheer to this candy-themed slot with holiday-themed symbols and a snow-covered background. It’s essentially the same game as the original Sweet Bonanza, but with a Christmas makeover, featuring jolly symbols like snowflakes and Christmas trees.

Η προσγείωση τριών ή περισσότερων συμβόλων scatter (η μηχανή τσίχλας) θα ενεργοποιήσει τη λειτουργία δωρεάν περιστροφών. Μπορείτε να κερδίσετε από 10 έως 35 δωρεάν περιστροφές, ανάλογα με το πόσα scatter θα πετύχετε. Κατά τη διάρκεια αυτού του γύρου, τα σημεία πολλαπλασιαστή παραμένουν ενεργά, ενισχύοντας τις δυνατότητές σας για μεγάλα κέρδη. Ο κουλοχέρης Sugar Rush 1000 μοιάζει με έκρηξη σε εργοστάσιο γλυκών. Είναι πολύχρωμο, διασκεδαστικό, φωτεινό και φορτωμένο με άπειρα ζαχαρωτά γλυκά. Μετά από μερικές περιστροφές, θα ψάχνετε για τη μυστική σας κρυψώνα με τα ζελεδάκια.

http://www.v0795.com/home.php?mod=space&uid=2190916

Τα ζωντανά γραφικά και οι ομαλές κινήσεις καθιστούν το Sugar Rush 1000 ελκυστικό. Οι παίκτες που αναζητούν διαδραστικά slots με μοντέρνες πινελιές θα απολαύσουν τα καινοτόμα χαρακτηριστικά και τον ελκυστικό σχεδιασμό του. Αυτό το δυναμικό, πλούσιο σε χαρακτηριστικά παιχνίδι πρέπει να είναι στη λίστα σας για μια συναρπαστική και ποικίλη εμπειρία παιχνιδιού. Κουλοχέρηδες Δωρεάν Παιχνίδι Shining Hot 5 από Pragmatic Play Συνδεθείτε μαζί μας Σημειώστε ότι για την πρόσβαση σε παιχνίδια με πραγματικά χρήματα, πρέπει να έχετε ηλικία 18 ετών ή άνω και να συμμορφώνεστε με τους κανονισμούς και τους όρους του κάθε καζίνο.

The sagacity in this piece is exceptional.

buy colchicine paypal

Najpopularniejsze kasyno Operator posiada ponad 10 tysięcy slotów, w tym Aviator. Dla fanów bardziej złożonych gier dostępna jest ruletka, poker, stoły na żywo i loterie. Obecnie strona oferuje kod promocyjny BETMORE z nagrodą do 1025 $. Oczywiście po wpłacie i obstawieniu. Mieszkańcy Kolumbii, Indonezji, Indii i Holandii najczęściej wybierają 1Win. Opracowany przez Spribe, Aviator przenosi grę w kasynach online na zupełnie nowy poziom dzięki innowacyjnemu formatowi. Gra opiera się na mechanice curve crash, która szybko stała się popularna wśród graczy ze względu na swoją prostotę i niezawodność. Choć nie jest to jedyna taka gra, w przeciwieństwie do innych podobnych tytułów, Aviator ma o wiele więcej do zaoferowania, angażując graczy swoimi unikalnymi funkcjami.

https://www.hipnoterapibandung.com/vulkan-vegas-w-polsce-jak-dziala-cotygodniowy-reset-bonusow/

Aviator Mostbet działa na podstawie legalnej licencji na gry online i przestrzega surowych przepisów, aby zapewnić uczciwe, bezpieczne i przejrzyste środowisko gry dla wszystkich graczy. Priorytetowo traktujemy odpowiedzialne praktyki hazardowe i stosujemy środki, które pomagają graczom zachować kontrolę: Latest EpisodeMay 29, 2025 Dla graczy, którzy nie chcą instalować aplikacji, alternatywą jest przeglądarkowa wersja mobilna. Mobilna strona oferuje pełną funkcjonalność, taką jak rejestracja, logowanie, zakłady sportowe, kasyno na żywo, płatności oraz dostęp do promocji. Pobieranie Mostbet nie jest wymagane — wystarczy uruchomić witrynę w przeglądarce mobilnej, aby korzystać z wszystkich opcji konta bez instalacji plików APK. Boomerang Casino Test5 ️ Online Spielcasino Bewertung 2022 Read More »

These days, it feels like football or soccer (as it is known in the US) is everywhere! Are you enjoying the FIFA Women’s World Cup in France? What about the exciting Copa América? Are you following the Total Africa Cup of Nations? If you like the game and want to expand your Spanish vocabulary of football terms, this lesson introduces some of the most common football soccer vocabulary words in Spanish. When it came to the fourth for each country, Sergio Ramos, who had blazed high over the bar in the Champions League semi-final shootout, clipped in a la Pirlo. “It seems to be fashionable now,” Del Bosque said. “I was delighted with it.” Bruno Alves then thumped his off the underside of the bar and away. As the ball bounced free, it took Portugal’s chances of reaching the final with it.

https://warriors-me.com/review-del-juego-balloon-de-smartsoft-gaming-para-jugadores-en-peru/

Penaltis ShootOut destaca por sus gráficos vibrantes y animaciones fluidas que recrean la emoción de un estadio lleno de aficionados. Cada gol es celebrado con efectos visuales y sonoros que aumentan la adrenalina, haciendo que cada sesión de juego sea una experiencia inolvidable. El mismo desarrollador, Evoplay ha creado una secuela interesante y divertida para los máximos aficionados a este tipo de juego. En Penalty Shoot out Street podrás disfrutar de una banda sonora y animaciones distintas. La gran diferencia es que en esta versión podrás disparar el balón a la dirección que prefieras. Participa en el Torneo copa craze. Apuesta en tus juegos de casino favoritos y obtén una parte de 60.000€ en premios. Sé uno de los 600 ganadores a este premio. ¿Estás listo para ganar? 1win Penalty Shoot Out es una de las mejores opciones que podrás encontrar en el mercado de apuestas en Argentina, esta plataforma te ofrece un gran panel de bonos y promociones, desde la oferta de bienvenida del 500% en primeros depósitos hasta un app móvil para jugar desde cualquier parte.

This is the big-hearted of writing I rightly appreciate.

https://proisotrepl.com/product/methotrexate/

شحن 1XBET مجانا. 5 تعليقات إذا كنت من عشاق ألعاب الطيران وتبحث عن تجربة مثيرة وممتعة فإن تحميل لعبة هكر 1xbet التفاحة مجانا يمكن أن يكون خيارا رائعا بالنسبة لك تعتبر هكر لعبة Crash 1xbet مجانا من أفضل العاب الطيران المتوفرة في السوق حيث تمتاز برسوماتها المذهلة والواقعية وتحاكي تجربة القيادة الفعلية بأقصى درجة دقة. بهذه الطريقة يمكن إنشاء حساب 1xBet والدخول على خيارات الألعاب ثم اختيار لعبة كراش predictor aviator. يمكنك البدء في العب والرحح من ألعاب 1xBet ، أو القيام بالمراهنات، قط قم بالتعرف على استراتيجيات الربح حتى تتمكن من الاستفادة وربح الأموال في كل مرة تلعب فيها.

https://maatravels.co/%d9%85%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%ac%d8%b9%d8%a9-%d9%84%d8%b9%d8%a8%d8%a9-aviator-%d9%81%d9%8a-%d9%83%d8%a7%d8%b2%d9%8a%d9%86%d9%88%d9%87%d8%a7%d8%aa-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a5%d9%86%d8%aa%d8%b1%d9%86%d8%aa-%d8%a8%d8%a7/

كل مستخدم ليس لديه حساب بعد لديه الفرصة لكسب مكافآت إضافية. يكفي استخدام الرمز الترويجي 1xBet 1XARPLAY عند إنشاء الحساب. سيمنحك رمز المكافأة 10 رهانات مجانية، يمكنك إنفاقها في لعبة Lucky Jet بعد إيداع مبلغ لا يقل عن 10 دولارات. “بيتي اتخرب وما أخدتش العبرة من كل مرة وعليا ديون مش عارف هعمل فيها إيه”.. تلك كانت مقدمة رواية أحد ضحايا ألعاب المراهنات مع لعبة “الطائرة”، التي خسر فيها كل ما يملك، وسحبته إلى الهاوية. تدور أحداث اللعبة على الإنترنت ، التي طورتها Spribe ، حول طائرة صغيرة تكسب المال. أولاً ، يجب أن تشاهد الطائرة تقلع ثم تضع رهاناتك في لعبة الرهان. أخيرًا ، اسحب أرباحك حتى تختفي الطائرة.

Thanks on putting this up. It’s understandably done. https://hardwareforums.com/proxy.php?link=https://roomstyler.com/users/adipe

https://t.me/s/Official_1win_kanal/300

The US biopharmaceutical company has scored a win in a long-running legal battle with… The Hack Mines has been a recurring theme among players who want to increase their chances of winning. Cheat Mines Betting is a common expression in this context, but it involves several approaches and tools. Here are some of the most common methods: Yes, players can customize their number of mines and use autoplay to streamline gameplay in Mines. Our Philippines online casino license shows our dedication to providing an exceptional and secure online casino experience. Join us at Peso88 Casino, where your enjoyment and safety are our priorities. The provider will offer customized Live Casino environments to Juega en Línea Features of the PHMines App: Register today to unlock exciting bonuses and promotions! Creating an account is quick and easy—just fill out the secure registration form. Join the PHMines community and start your gaming journey right now!

https://demo.nitmag.com/comparing-coin-bundle-prices-in-balloon-slot-by-smartsoft/

Most Asked Questions while Booking 4 Star Hotels in Montceau-les-Mines See more: Intermarché and Auchan to buy more than 300 Casino stores in France Own-brand products can cost up to 30% less than branded items, but are often of poorer quality, a new study claims Casino Barrière Couples Massages Kit Spike Best countries to visit in February Product returns are accepted within 7 days of receiving your order. Product returns are eligible for a refund if your return meet all the following criteria More information about the returns policy TSL’s products are guaranteed against any operation defect resulting from any material, manufacturing or designing defect subject to the following provisions. This warranty applies for 2 years after the delivery of the product in accordance with article L. 217-4 of the french Consumers’ Code. Replacement parts available, 5 years. Manufacturing defects are covered subject to normal maintenance and normal use (hiking). More information about the warranty terms and conditions

O Big Bass Splash tem uma estrutura de tambores de 5×3 e 10 linhas de pagamento possíveis. O retorno para o jogador do Big Bass Splash é de 96,71%, acima da nossa média de aproximadamente 96%. Jogue Big Bass Bonanza, o jogo do pescador, no cassino da KTO e ganhe até 2.100x o valor da sua aposta! Devido à alta volatilidade, o Big Bass Splash concederá pagamentos maiores com menor frequência. O Aviator é provavelmente um dos principais jogos desta categoria por entregar ao usuário uma experiência bem animada, é preciso sair do avião antes que o mesmo vá para longe e a decisão precisa ser feita em milésimos de segundos. Gire os slots demo da Pragmatic Play agora no DemoSlotsFun. Sem cadastro, sem limite — só caos puro e giro nervoso. Chegou até aqui? Então toma respeito. Esse site é caos organizado: mais de 50 provedores entregando giros demo recheados de emoção, recursos absurdos e trilha sonora de arrepiar. Tá esperando o quê? Escolhe um slot e detona esse carrossel digital!

https://www.queenzzz-aim.com/site-para-jogar-aviator-o-que-considerar-antes-de-apostar/